Regardless of the type of camera he has in his hand, a local documentary filmmaker and photographer loves to preserve special moments in time.

Growing up in Wisconsin, Augusta resident Mark Albertin knew little about the South other than the often distorted portrayal he saw of it on film and television. However, his maternal grandmother was born and raised in Augusta, so he had a connection to the region.

He moved to Georgia in 1986, but he strengthened his ties to the South even more when he made his first video – a tribute to his grandmother – as a birthday gift for his own mother years ago.

“It all comes back to the roots of where it started,” says Albertin. “I never met my grandmother, but I wanted to know who she was. My mother talked about us like we were soup. She said we came from good stock.”

“It all comes back to the roots of where it started,” says Albertin. “I never met my grandmother, but I wanted to know who she was. My mother talked about us like we were soup. She said we came from good stock.”

As it turns out, that dive into his ancestry was a gift to himself as well. After making the video, Albertin started Scrapbook Video Productions in 2000 to produce documentary films. He made a $30,000 investment in equipment, including a high-end video production camera and editing equipment, to start the business.

“I was bitten by the bug, and I wanted to do bigger and better things,” he says. “It allows me to do the projects that I want to do.”

Many of his productions, which range from stories of towns to noted individuals, have aired on PBS and received awards from film festivals across the country. His newest film, Finding Home – 20th Century Voices of Augusta is slated to premiere late this year or early next year. Albertin had planned to hold the premiere in August at Imperial Theatre, but it has been postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Many of his productions, which range from stories of towns to noted individuals, have aired on PBS and received awards from film festivals across the country. His newest film, Finding Home – 20th Century Voices of Augusta is slated to premiere late this year or early next year. Albertin had planned to hold the premiere in August at Imperial Theatre, but it has been postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

This film is a revised version of Augusta Remembers, which aired on Georgia Public Television in 2000. For the original documentary, Albertin interviewed his grandmother’s contemporaries about life in Augusta from the early 1900s to the 1940s. In Finding Home, Albertin has added interviews with local residents about living in the area from the 1950s through the 1980s.

“The documentaries that include oral histories are essential. We need as a nation to listen to our older people,” Albertin says. “It gives us comfort and support and makes us feel better to know that other people lived through hard times.”

School of Hard Knocks

School of Hard Knocks

Albertin, who also is a professional photographer, is a self-taught filmmaker. His original skill set is in color separation for the four-color printing process. That process is flat and two-dimensional, he says, so he started attending video boot camp training classes in Atlanta and Charlotte in his spare time.

In addition, he says, “I went to the school of hard knocks where you’re up until three in the morning trying to figure something out.”

Like many documentary filmmakers, Albertin says, he followed the lead of celebrated documentarian Ken Burns, who uses archival footage and photographs, to transform a film from a product with boring narratives and static images into something more compelling.

“Ken Burns showed us that you can use voices, sound effects and music from the time period,” says Albertin. “The key is to pull people in, and you can do that with writing, sound effects, voiceovers and real people. The audience needs to engage with the film and feel a connection to the people and the subject matter.”

Albertin enjoys every aspect of filmmaking from adding movement, sound and sound effects to conducting interviews and writing the scripts. “It’s a blast to do this stuff,” he says. “It allows me to really be creative.”

He spends 80 percent of his time on video, 15 percent on photography and 5 percent writing. “I love all three of those things, and I find ways to mesh them together,” Albertin says.

He also likes to meet people and talk to them, and he has learned firsthand from people’s oral histories what it was like to live through trying times such as the Dust Bowl or the Holocaust.

“If these people are good storytellers, they take you somewhere you’ve never been,” says Albertin. “I can feel their pain when they tell me their stories. People in the twilight of their lives want to talk about their experiences for posterity.”

He spends a lot of time doing research and tracking down people, and he wants those he interviews to feel like they have been heard and respected.

“The people that know that history are the ones that are going to come and watch a premiere,” says Albertin. “The main audience that I’m appealing to is age 70-plus. To capture their stories and preserve them is a wonderful thing to do. The feeling that I get in my heart and soul is something I can’t explain.”

He often relies on narration early in his documentaries to set the stage, and he says the narrator can “make or break” a film.

“Each film has a different formula, depending on what the storyline is,” Albertin says. “Sometimes you start with the ending first. They’re not always chronological.”

Feeding the Senses

Feeding the Senses

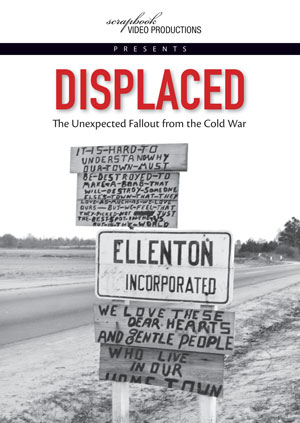

Some of his other documentaries include Displaced: The Unexpected Fallout from the Cold War, about the development of the Savannah River Site that displaced more than 5,000 residents in rural South Carolina communities, and Discovering Dave: Spirit Captured in Clay, about a literate slave potter who lived in Edgefield, South Carolina and wrote verse and poetry on his pots. He also has done a Remember series about various towns such as Augusta and Savannah in Georgia, St. Augustine and Jacksonville in Florida, Beaufort, North Carolina and Topeka, Kansas.

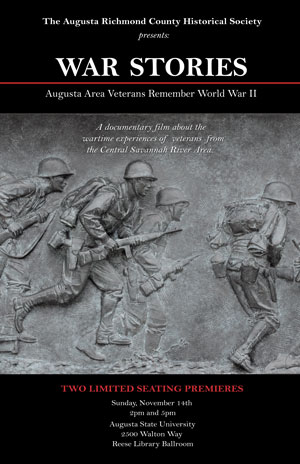

He made the award-winning War Stories – Augusta Area Veterans Remember World War II, in which he spent four years interviewing local veterans from all branches of the military to highlight their World War II experiences.

This project began as part of the Veteran’s History Project, which was undertaken by the Augusta Richmond County Historical Society to add to the Library of Congress Veterans History Project. To collect these oral histories, Albertin went to Brandon Wilde and interviewed 20 veterans a day.

“You’re not going to get rich making documentaries,” says Albertin, who also does promotional spots and commercial videos. “It’s the satisfaction of preserving something and creating something that makes people laugh or cry.”

The reaction to his work is something that Albertin usually experiences secondhand, however. He says he never sits in the theater when his films premiere. Instead, he dispatches his wife to join the audience while he settles in the lobby.

Maybe he should rethink that plan, however, because his wife usually tells him he should have been in the theater to see the positive reaction to his films.

“When I’m gone, I will have hopefully left something behind that people can learn from,” says Albertin. “Film was, and hopefully one day, will become a social event again. I love film because you’re seeing two things happen. You hear and see, so you’re getting two senses fed at once.”

Documentaries need to be fair and balanced, he says, and he covers difficult issues such as racial injustice in his films.

“It’s something we need to see and hear. We need to understand that it can happen again, and we need to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” says Albertin. “Everybody has their own angle on what happened.”

Blending In

When he photographs a subject, Albertin approaches it from different viewpoints as well.

“Photography is an extension of video,” he says. “It’s trying to tell a story with pieces in an artistic manner. It’s all about the storytelling. Sometimes one picture is all you need. Sometimes you need multiple pictures with multiple angles.”

His love of photography dates back to his childhood when he would borrow cameras from his father, who was a medical illustrator. And that interest “never went away.”

“I love going out and playing with old cameras. The results you get are totally different from digital,” says Albertin.

He prefers photographing landscapes to people because he finds it less stressful. “Those places are where I find peace,” he says of landscapes. “They’re getting harder and harder to find.”

He says it’s pleasant to go outside – other than having to lug all the gear around. He likes to capture the light or early morning dewdrops on leaves. When he goes into the woods, he usually is alone.

“You have to sit still for a while to blend into a setting,” Albertin says.

He is just as likely to shoot in black and white as he is in color, depending on what he wants to accomplish.

“To me, color is really at its best in the spring,” says Albertin. “Black and white is a more spiritual medium. I use black and white when I want people to notice the object and the composition. Black and white can do amazing things if you use the right filter.”

Whether he is making films or photographs, Albertin hopes his work provides people with an escape.

“I want people to be able to leave their stress, their worries and their problems behind and get into another place and see what I saw,” he says. “To me, that is another way to do something good.”

By Leigh Howard