From kayaks to fly fishing rods, an Evans father and son create functional wood works of art.

About 10 years ago, Evans resident Bradley Bertram, aka one of the Eye Guys, was looking for something to do to fill the cold-weather months. Or, perhaps more specifically, his wife, Paige, was looking for something for him to do, so for Christmas she gave him the plans and materials to build a wooden kayak.

“Shortly after that, she described herself as a ‘kayak widow,’” Bradley says.

Especially since the 14-month project ended up spanning two winters. However, it wasn’t a solitary endeavor. Bradley’s then-adolescent son, Collin, who is now a 22-year-old college senior, got involved as well. He had built a couple of small model boats, but he was ready for a bigger, better challenge.

“I got interested in it right away. I like building things, boats, boating and fishing,” says Collin. “We jumped from building small model boats a foot long to building actual boats. I’m always in the garage helping with something, so it morphed into that.”

The Eyes Have It

The Eyes Have It

The first kayak they built was an 80-pound tandem. However, during covid in 2020 and 2021, when many of us were binge-watching TV shows, they decided to build a 40-pound, one-person kayak. The newest vessel sports a pair of eyes on its deck, so naturally, Bradley dubbed it their “KeyeYAK.”

“I’m the king of dad humor,” he says. “My specialty is corneal surgery, so I’m the king of ‘corn’-ea.”

The Bertrams built the single KeyeYAK in six months. “It was easier to make than the first one, but adding the eyes made it harder,” says Bradley. “We turned a hatch into an eye, and every part of the eye is a different wood with a different color.”

The pupil is walnut; the iris is western red cedar; the sclera is Alaskan yellow cedar.

“Each kayak has a set of plans, but you can do what you want with them,” Bradley says.

In fact, their next kayak will be a racing-style model with an inlaid blue heron on the deck.

To construct the kayaks, the Bertrams use the stitch-and-glue method to stitch pre-cut plywood panels together with wire and then glue the seams with a mix of epoxy resin and wood flour. Once the kayak is assembled, they trim the exposed wire. Then, to waterproof and strengthen the wood, they cover it in protective layers of fiberglass.

“Most of the weight is in the epoxy,” says Bradley. “We put five pounds of epoxy in each end of the kayak. If we run into something, it’s protected.”

The hull is made of 8-inch mahogany plywood, and the deck consists of cedar and walnut strips.

The hull is made of 8-inch mahogany plywood, and the deck consists of cedar and walnut strips.

“We’ll do 30 to 60 minutes of work, and then we have to wait while it dries,” Bradley says. “There’s a lot of ‘hurry up and wait.’”

Father and son also have developed an effective division of labor for their projects.

“Collin gets the jobs where a limber person is needed,” says Bradley. “He crawls in the hull to put in the filler and epoxy.”

He also is in charge of sanding the wood, a practice that dates back to his youth when he enjoyed dressing the part in surgical gown, goggles and ear protectors.

“At that age, using a power tool for hours is the best thing in the world,” Collin says. “Not so much now, though. It’s the most tedious part of the project.”

The younger Bertram doesn’t seem to mind, though. “We work well as a team,” he says. “We coordinate with each other all the time. My dad will work on the kayaks when I’m at school, and I work on them when he’s at work.”

Bradley says a lot of planning – and psychology – are involved in the construction process.

“Psychology comes into play in boat building. You get very obsessive-compulsive about it,” he says. “You question if it’s good enough, or if you should start over. We learned not to set a deadline because then it becomes work, and that takes the fun out of it.”

“Psychology comes into play in boat building. You get very obsessive-compulsive about it,” he says. “You question if it’s good enough, or if you should start over. We learned not to set a deadline because then it becomes work, and that takes the fun out of it.”

‘Good for the Soul’

Woodworking is as soothing as paddling on open water for the Bertrams, and Collin loves the creativity as well.

“You start with a tree, and you can manipulate it yourself into almost anything,” he says.

Bradley appreciates the yin and yang of their avocation.

“Part of it is very mindful. You really have to plan and think about what you’re doing so you don’t mess it up,” he says. “Then there’s part of it, like sanding, that’s mindless. Mindless work is good for the soul.”

While they love to take their kayaks out on the water, they’re always concerned that they might damage them by inadvertently paddling over a rock.

“In fact, both hulls have been repaired from doing just that,” says Bradley.

The risk to their handiwork doesn’t deter them from paddling, however.

“If you go through everything it takes to build it, you’re going to use it,” Collin says. “Open water is better for a wood kayak. You don’t want to take it around rocks or on rapids. If you scratch the hull or the top, it takes three days of work to bring it back to what it was.”

Besides beauty and durability, the Bertrams say wood kayaks have other benefits as well.

For instance, Bradley says, “The small one is lighter than a fiberglass counterpart.”

“You can cut through the water fast in a wood kayak. A lot of plastic kayaks have a fin or a rudder,” Collin says. “You don’t have to worry about a wood kayak going one direction or the other. It’s going to go straight.”

‘Then You Go Fishing’

‘Then You Go Fishing’

The Bertrams have made other items, including custom fly fishing rods that they crafted three summers ago at a class they took together at Oyster Bamboo in Blue Ridge, Georgia.

While Bradley built a rod with a tortoiseshell finish and rattan grip, Collin crafted a solid wood rod with a cork grip.

“There’s constant anxiety that you’re going to do something wrong,” Bradley says. “You either love it or hate it.”

“If you’re off by one one-thousandth of an inch, it will take you another day to redo it,” adds Collin.

They worked on their rods all day from Monday through Saturday, and for the record, they didn’t mess up. “And then you go fishing on Sunday,” says Bradley.

Collin caught a 22-inch rainbow trout with his brand new rod. “You could still smell the varnish on the rod,” his father says.

They also have made cutting boards for gifts, but they don’t sell their work. They built a river table headboard for Collin’s bed out of maple wood, and currently, they’re working on a maple river table for the screened porch at their house.

“When I’m building something, it’s out of need. I want something functional,” says Collin.

Family Legacy

Bradley also likes the idea of creating family heirlooms to pass down to his children. In fact, when Collin’s twin sister, Carter, left home for college, she refinished her grandfather’s desk and took it to school with her.

“My dad built the desk in a woodshop class when he was in high school in 1930,” says Bradley.

The kayaks are destined to become part of the Bertram legacy as well.

“I’ve instructed that they are to never leave the family,” Bradley says.

By Betsy Gilliland

After all, it was hard for the elder Ciamillo to miss his son’s growing interest in working with wood.

After all, it was hard for the elder Ciamillo to miss his son’s growing interest in working with wood. The physician has found that he sometimes uses similar skills sets when practicing medicine and working with wood.

The physician has found that he sometimes uses similar skills sets when practicing medicine and working with wood. Star of the Show

Star of the Show The Ciamillos also designed a wine flight for Cork and Flame and made a walnut tableside cutting board, as well as a whiskey flight, for the Evans restaurant.

The Ciamillos also designed a wine flight for Cork and Flame and made a walnut tableside cutting board, as well as a whiskey flight, for the Evans restaurant. The Ciamillos currently work out of a 2,100-square-foot shop in Martinez, where the younger Ciamillo spends about 16 hours a day woodworking.

The Ciamillos currently work out of a 2,100-square-foot shop in Martinez, where the younger Ciamillo spends about 16 hours a day woodworking. He enjoys 3D modeling and 3D design, and he taught himself how to operate their CNC (computerized numeric control) machine. This machine cuts or moves various materials, including wood. Instead of being controlled by a human operator, the machine’s movements are calculated and carried out by a computer on a pre-programmed path.

He enjoys 3D modeling and 3D design, and he taught himself how to operate their CNC (computerized numeric control) machine. This machine cuts or moves various materials, including wood. Instead of being controlled by a human operator, the machine’s movements are calculated and carried out by a computer on a pre-programmed path.

Go with the Flow

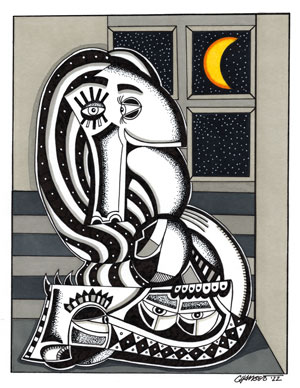

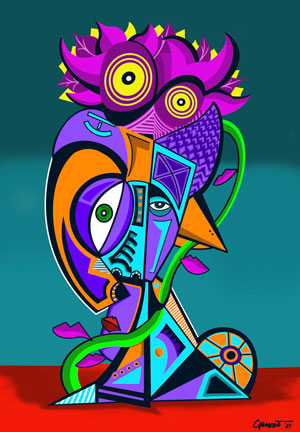

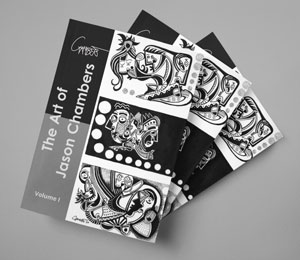

Go with the Flow “I usually carry a sketchbook with me everywhere I go. At the end of the day, I see what I’ve done. The next morning I put it on watercolor or Bristol paper,” says Boland. “I just like creating characters. It’s really fun to have them occupy a space on paper and not just scribbled in a notebook.”

“I usually carry a sketchbook with me everywhere I go. At the end of the day, I see what I’ve done. The next morning I put it on watercolor or Bristol paper,” says Boland. “I just like creating characters. It’s really fun to have them occupy a space on paper and not just scribbled in a notebook.”

“We’re always on the lookout for emerging artists,” says Boland.

“We’re always on the lookout for emerging artists,” says Boland. Dream Journal

Dream Journal

Operation Double Eagle is a nine-week skills development program at Augusta Technical College that connects veterans and transitioning active duty service members to a network of employers seeking “job-ready” veterans for nationwide career opportunities.

Operation Double Eagle is a nine-week skills development program at Augusta Technical College that connects veterans and transitioning active duty service members to a network of employers seeking “job-ready” veterans for nationwide career opportunities. Tindell, who lives in Evans and served in the Army for 20 years, talked to Weber about Operation Double Eagle. Although a session had started a week before their conversation, Tindell squeezed the veteran into the program.

Tindell, who lives in Evans and served in the Army for 20 years, talked to Weber about Operation Double Eagle. Although a session had started a week before their conversation, Tindell squeezed the veteran into the program. And that wasn’t the last time he put his director supervisor, Brett Ambrose, on notice that he’s coming after his position. Ambrose, a Landscapes Unlimited project superintendent, appreciates the ambition.

And that wasn’t the last time he put his director supervisor, Brett Ambrose, on notice that he’s coming after his position. Ambrose, a Landscapes Unlimited project superintendent, appreciates the ambition. Operation Double Eagle is the brainchild of Scott Johnson, president and chief executive officer of the Warrior Alliance. During his 20-plus years as a corporate executive, he worked with wounded warriors and saw a contingent of the veteran population that was unemployed or bouncing from job to job.

Operation Double Eagle is the brainchild of Scott Johnson, president and chief executive officer of the Warrior Alliance. During his 20-plus years as a corporate executive, he worked with wounded warriors and saw a contingent of the veteran population that was unemployed or bouncing from job to job. With local assets such as Fort Gordon, a rich military tradition, the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center and Augusta National Golf Club, Johnson says this area has been the ideal place to build the program.

With local assets such as Fort Gordon, a rich military tradition, the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center and Augusta National Golf Club, Johnson says this area has been the ideal place to build the program. “We have everything that a larger golf course operation would have,” says Evans resident O’Neil Crouch, a former golf course superintendent and Operation Double Eagle program director. “They get to learn real-world problems. If we have to, we create problems.”

“We have everything that a larger golf course operation would have,” says Evans resident O’Neil Crouch, a former golf course superintendent and Operation Double Eagle program director. “They get to learn real-world problems. If we have to, we create problems.”

A local avian sanctuary is spreading its wings

A local avian sanctuary is spreading its wings Keeping a Promise

Keeping a Promise “I made a promise that somehow, someday, I would make it up to every bird that needed a home,” he says.

“I made a promise that somehow, someday, I would make it up to every bird that needed a home,” he says. The facility also has started to work with military personnel who are dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder. Animal companions like parrots can be a source of joy and wellness for people with PTSD.

The facility also has started to work with military personnel who are dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder. Animal companions like parrots can be a source of joy and wellness for people with PTSD.